In the 1980s, pain specialists argued there was a “low incidence of addictive behavior” associated with opioids and pushed for their increased use to treat long-term pain. For 20 years, pharmaceutical manufacturers, consultants, salespeople, entrepreneurs, and doctors collaborated to sell opioids in remarkable quantities. The result was a surge in spending for opioids and, more importantly, the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people and the addiction of a million others.

The primary driver of this phase of “pain management” was “the shrewd targeting of a market niche by a pharmaceutical manufacturer, the cost-benefit calculations of insurance carriers, and the creative entrepreneurship of drug traffickers,” according to an article published in the American Journal of Public Health. Opioids made it to the top of the list of workers’ compensation drug spending.

As the death count and addictions soared, public outcry led to legislative and insurance practice reforms fueled by massive lawsuits and waves of crackdowns on pill mills. Spending on opioids in workers’ compensation started a decline over the last decade as unbridled opioid prescriptions fell out of vogue. The opioid mole was smacked on the head.

But drug companies, doctors, pharmacies, and entrepreneurs were not about to give up a good revenue stream so easily. Under the guise of new treatments “intended to reduce reliance on opioids,” a new mole popped up – compounded pain creams (“CPC’s.”)

In just a few years, CPC’s moved from rarely encountered in workers’ compensation to the dominant cost driver. These concoctions had little scientific support, no FDA approval, and questionable efficacy, but aggressive marketing and flat-out greed propelled CPC spending to the level of a national crisis. These creams could be mass-produced for under $100 a tube but were sold as if they were customized to specific patients with charges of up to $13,000 a month. It took a decade of lawsuits, arrests, forfeitures, litigation, and legislative reforms before the CPC mole was whacked down. Spending on CPC’s plummeted from 10 percent of all workers’ compensation medical spending to 1 percent.

But again, another mole popped up to replace CPC’s. The new mole is “dermatologicals” – medications applied to the skin by patch, gel, cream, or drop. Rushing to fill the money-making void left open by restrictions on opioids and CPC’s, dermatologicals are now all the rage. Like CPC’s, there is a paucity of empirical evidence that these products provide significant long-term pain relief, and like CPC’s, they are moved not by patient demand but rather, they are heavily pushed to patients by some doctors, pharmacies, and entrepreneurs. Also, like CPC’s, they can cost up to $3,300 per month for drug formulations that are often already available over the counter (“OTC”) for under $10. Because states like Pennsylvania have no drug formularies and no fee schedules for drugs, these drugs can be sold for high prices, and sales are growing quickly.

But again, another mole popped up to replace CPC’s. The new mole is “dermatologicals” – medications applied to the skin by patch, gel, cream, or drop. Rushing to fill the money-making void left open by restrictions on opioids and CPC’s, dermatologicals are now all the rage. Like CPC’s, there is a paucity of empirical evidence that these products provide significant long-term pain relief, and like CPC’s, they are moved not by patient demand but rather, they are heavily pushed to patients by some doctors, pharmacies, and entrepreneurs. Also, like CPC’s, they can cost up to $3,300 per month for drug formulations that are often already available over the counter (“OTC”) for under $10. Because states like Pennsylvania have no drug formularies and no fee schedules for drugs, these drugs can be sold for high prices, and sales are growing quickly.

An example is Nulido, a patch or gel with 4 percent lidocaine and 1 percent menthol as the active ingredients. This formulation is not novel – it has been used in various products for decades. IcyHot is a similar formulation sold in drug stores over the counter for under $30. But if you buy the Nulido version of the formulation, the charge is often between $500 and $3,500 per month. Why would a patient seek it for $3,500 a month when the same formulation is available at the corner store for 95 percent less? The answer is obvious – it is not being used because patients are seeking it out, it is being used because doctors, pharmacies, and entrepreneurs are pushing it. Just like with opioids and CPC’s, there is a fortune to be made selling hope to people complaining of pain, and the patients are eager to rely on whatever the doctor recommends.

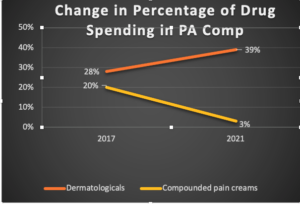

This chart shows the nearly perfect correlation between the drop in CPC spending in workers’ compensation and the rise in dermatologicals spending. The new mole is nearly a perfect substitute for the last one.

There are ways to whack the new dermatologicals mole but using traditional routes such as utilization review will probably not work. These drugs can provide some people with some relief, and UR reviews will likely find them to be reasonable and necessary. The issue is not whether the drug is appropriate; the issue is whether the patient was steered or otherwise urged to use a version of a product at a 900 percent markup over other available equivalents.

Just as some cancers are treated by cutting off blood flow to the tumor, the best route to restricting the proliferation of dermatologicals for pain is by attacking the flow of money to the key players. We need to expose the roles and involvement of the players, direct challenges to the pricing, as opposed to the reasonableness and necessity of the drugs provided, and to use data to connect the dots between players who are creating both the supply and the demand. If we understand how the mole moves and can predict when and where it will pop up, we can more effectively whack it.

One challenge is companies tend to rely on existing vendors and known methods even when the problem is novel and new. For example, using pharmacy benefits managers (PBM’s) to negotiate lower prices for dermatologicals is like trying to bring down the cost of groceries by using more coupons. It has an impact but at the wrong end of the problem. Using drug repricing vendors won’t work either unless they relearn what to look for and learn how to use alternatives to average wholesale price (AWP) like those developed at Chartwell Law. The starting point is exposing the issues, prices, and players to the relevant community. Next, we need data collaboration and sharing by carriers, TPA’s (third-party administrators), repricers, and PBM’s to reveal patterns that we can use to predict where the mole will pop up. This may not be easy as each party may have an interest in maintaining the status quo.

But even as we hammer away at the dermatologicals mole, we can already see several others ready to pop up – most involving costly medical devices and equipment. Winning will require continuous learning from shared data, predictive analysis, and focus on the money flow behind the game.

There are ways to whack the new dermatologicals mole but using traditional routes such as Utilization Review (UR) will probably not work. These drugs can provide some people with some relief, and UR reviews will likely find them to be reasonable and necessary. The issue is not whether the drug is appropriate; the issue is whether the patient was steered or otherwise urged to use a version of a product at a 900 percent markup over other available equivalents.

Just as some cancers are treated by cutting off blood flow to the tumor, the best route to restricting the proliferation of dermatologicals for pain is by attacking the flow of money to the key players. We need to expose the roles and involvement of the players, direct challenges to the pricing, as opposed to the reasonableness and necessity of the drugs provided, and to use data to connect the dots between players who are creating both the supply and the demand. If we understand how the mole moves and can predict when and where it will pop up, we can more effectively whack it.

One challenge is companies tend to rely on existing vendors and known methods even when the problem is novel and new. For example, using pharmacy benefits managers (PBM’s) to negotiate lower prices for dermatologicals is like trying to bring down the cost of groceries by using more coupons. It has an impact but at the wrong end of the problem. Using drug repricing vendors won’t work either unless they relearn what to look for and learn how to use alternatives to average wholesale price (AWP) like those developed at Chartwell Law. The starting point is exposing the issues, prices, and players to the relevant community. Next, we need data collaboration and sharing by carriers, TPA’s (third-party administrators), repricers, and PBM’s to reveal patterns that we can use to predict where the mole will pop up. This may not be easy as each party may have an interest in maintaining the status quo.

But even as we hammer away at the dermatologicals mole, we can already see several others ready to pop up – most involving costly medical devices and equipment. Winning will require continuous learning from shared data, predictive analysis, and focus on the money flow behind the game.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims

Why 2026 Is The Tipping Point for The Evolving Role of AI in Law and Claims  US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk

US Will Test Infant Formula to See If Botulism Is Wider Risk  Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus

Elon Musk Alone Can’t Explain Tesla’s Owner Exodus  UBS Top Executives to Appear at Senate Hearing on Credit Suisse Nazi Accounts

UBS Top Executives to Appear at Senate Hearing on Credit Suisse Nazi Accounts