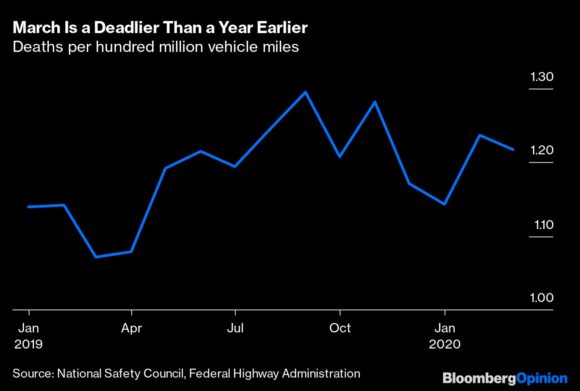

Almost three months into the coronavirus crisis finds U.S. highways with just a fraction of their pre-pandemic traffic. It would be natural to assume that should make driving safer, at least until the country is fully opened. But if anything, the roads may have gotten more dangerous.

As NPR recently reported, the National Safety Council has found that fatalities per mile driven were up 14% in March from a year earlier:

So what’s going on? Part of the problem could be that people are more stressed, especially when they go outside. Stress is distracting and might affect reflexes and judgment. Plus some people are probably driving in masks that reduce their peripheral vision.

Those might be understandable reasons. But it also looks as if drivers may be driving more recklessly. In particular, rush-hour driving speeds are up. And speeding has increased across the country, including in very high-speed categories, such as those caught driving at 100 mph or more.

Unfortunately, that’s probably in large part a result of our behavioral foibles.

With fewer cars on the roads, there’s less traffic congestion, which makes it physically possible to drive faster. And when people can drive faster, they do.

Some motorists, of course, really do want to put the pedal to the metal. But even drivers who aren’t angling to be in the next hyperkinetic “Fast & Furious” movie will speed up at least a little bit; there is, after all, real value to getting where you’re going faster.

Since the earliest theories of the economics of crime, it’s been known that people are more likely to do something like speeding when there’s less chance of getting caught. And even if police monitoring hasn’t really changed, many people probably think it’s gone down amid all the other tangible decreases in public activity.

Plus with fewer cars and pedestrians out and about, drivers probably feel they have more room for error and are less likely to have to react to an unexpected swerve by another driver or a texting jaywalker. More people driving alone because of social-distancing guideline could also account for the rise in risky driving; some drivers exercise less care when they don’t have passengers (although on the other hand, passengers can themselves be distracting).

And that’s not all: When driving, we often match our behavior to perceptual feedback from other cars. That means there’s a herd effect; when a few motorists speed others drive faster as well.

Taking all of this together, we get a behavioral cocktail that leads to less-than-ideal actions. But how should we break this feedback loop?

Police could step up patrolling, raising the probability that dangerous drivers would get caught. That said, this would only alter behavior if the change were clearly communicated to the public.

People are also more likely to take actions — such as safe driving — that contribute to the public good when others observe them. But with so few other people on the road, who’s going to witness drivers’ behavior?

One simple nudge that might help would be to put up more roadside signs that tell drivers their speeds. At minimum, this would make high speeds visible to drivers and at least to some other motorists. It might even give drivers a sensation of being watched, as those signs are often associated with police monitoring.

We could also give people signals about how much faster they’re driving than the average, perhaps by sending out letters to drivers based on data from speed cameras. Interventions like this have been effective in reducing energy usage.

It’s possible there’s a way to appeal to people’s better instincts and sense of social responsibility. That’s been tried for encouraging subway payments recently, with at least some success. Even better could be to introduce role models.

Of course we also might think about raising fines for speeding during lockdown. We don’t normally do that, but the coronavirus has changed so much about behavioral norms that it wouldn’t seem far-fetched. If we go that route, we have to be careful to make sure we don’t create or exacerbate equity issues: many of the people on the road at the moment are out driving because they have to for financial and family reasons, plus traffic stops are already a disproportionate burden on minorities and low-income drivers.

In any event, people’s behavior is unlikely to adjust without some sort of policy change. So the question shouldn’t be whether to intervene, but which route to take — and how fast.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Building Fortification And The Role of The Insurance Industry

Building Fortification And The Role of The Insurance Industry  Asbestos Lawsuits Prompt Vanderbilt Minerals to File Bankruptcy

Asbestos Lawsuits Prompt Vanderbilt Minerals to File Bankruptcy  AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers

AI Claim Assistant Now Taking Auto Damage Claims Calls at Travelers  Moody’s: LA Wildfires, US Catastrophes Drove Bulk of Global Insured Losses in 2025

Moody’s: LA Wildfires, US Catastrophes Drove Bulk of Global Insured Losses in 2025