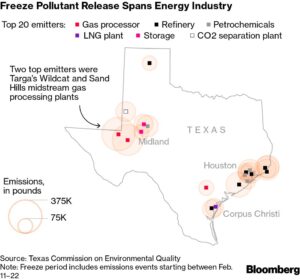

The polar blast in Texas earlier this year revealed a dirty secret in the most prolific U.S. oil field: Two under-the-radar natural gas plants that are a persistent source of pollution.

Natural disasters in the state often turn into environmental disasters, and February’s cold wave was no exception. Stricken by power outages and mechanical failures, industrial facilities burned off or released huge quantities of hazardous gases as they shut down. The worst culprits, however, weren’t the vast petrochemical complexes on the Gulf Coast but the two Permian Basin facilities that take raw gas from wells and purify it into sales-quality fuel.

The Wildcat and Sand Hills plants, both run by Houston-based Targa Resources Corp., accounted for almost 20% of the state’s total pollution during the freeze and nearly four times the amount emitted by the country’s biggest refinery, according to an analysis of state records that was carried out by Air Alliance Houston, Environment Texas and Environmental Defense Fund and reviewed by Bloomberg.

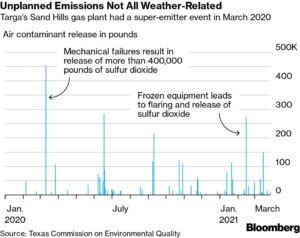

The winter storm wasn’t a one-off: The two plants have released hazardous gases above permitted levels more than 400 times since the beginning of 2019, according to filings with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. That’s equivalent to about once every two days. Targa didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

That two mid-sized processing plants can become super emitters underscores how the vast U.S. gas network is only as strong as its weakest link. Environmental goals adopted by producers and refiners count for little if the facilities holding the system together are vulnerable to breakdowns. The crisis triggered by the freeze has spurred notoriously regulation-averse Texas into action, with state lawmakers weighing bills that may require gas plants and pipelines to be winterized.

That two mid-sized processing plants can become super emitters underscores how the vast U.S. gas network is only as strong as its weakest link. Environmental goals adopted by producers and refiners count for little if the facilities holding the system together are vulnerable to breakdowns. The crisis triggered by the freeze has spurred notoriously regulation-averse Texas into action, with state lawmakers weighing bills that may require gas plants and pipelines to be winterized.

“When you have hundreds of emission events a year, is it really an upset or is it just usual operating conditions?” said James Doty, a former TCEQ mobile monitoring manager. “You would obviously expect more emissions from the biggest oil and gas facilities in the world than you would from these types of plants.”

State filings likely don’t even capture the scope of the pollution released during the storm. Companies are required to report hazardous compounds like benzene, hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide but not greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane.

Targa suffered major outages as a result the storm, with its operations at about half capacity during the 10-day period, Chief Executive Officers Matthew Meloy told investors on a Feb. 23 earnings call. He declined to provide any more detail and didn’t specify whether the problems were caused by the cold, power outages or both.

One reason for the high volume of emissions from gas processing plants is that the facilities are in short supply in the Permian, where supplies of the fuel have swelled as a byproduct of drilling for more-valuable oil in the past decade. As a result, the plants operate under extreme pressure and one mechanical fault can cause outages that lead to flaring, or burning off gas that has nowhere to go.

Click here to see emissions and other ESG data on the Bloomberg Terminal

“Gas processing plants are designed for continuous flow, so if you get unexpected outages on the outbound side, you have to start flaring immediately for all the gas that’s still incoming,” said Artem Abramov, head of shale research at Rystad Energy. “Infrastructure is super stretched, so when one plant goes offline, you have high line pressure” in the surrounding pipelines that collect gas from wells.

In a vicious cycle, that extra pressure can mean more outages. Loss of gas supply to power plants contributed to blackouts during the freeze, which in turn compounded operational problems at gas processors. There was “a complete collapse of general infrastructure,” Abramov said.

Targa’s TCEQ filings shed some light on what led to the plants becoming the state’s top polluters, emitting more than Exxon Mobil Corp.’s giant Beaumont and Baytown refining and petrochemical complexes combined.

“Sustained freezing temperatures” at Wildcat in Winkler County caused its amine, or acid removal, system to fail, meaning that the plant had to flare incoming gas for seven days straight, Targa said in a TCEQ filing. Separately, Targa reported it released 4.9 million cubic feet of gas over a 10-hour period after a “hydrate” — likely an ice blockage — was found in a pipeline near the plant. That’s about the same amount of gas used by 25,000 U.S. homes each a day.

“Sustained freezing temperatures” at Wildcat in Winkler County caused its amine, or acid removal, system to fail, meaning that the plant had to flare incoming gas for seven days straight, Targa said in a TCEQ filing. Separately, Targa reported it released 4.9 million cubic feet of gas over a 10-hour period after a “hydrate” — likely an ice blockage — was found in a pipeline near the plant. That’s about the same amount of gas used by 25,000 U.S. homes each a day.

At Sand Hills in Crane County, problems also began on Feb. 14, when pressure dropped “due to a loss of air compressors caused by freezing in the lines,” according to Targa’s report to TCEQ. Power outages compounded the issue and caused unauthorized emissions to last for four and a half days. Separately, Sand Hills reported that its CM-14 acid gas compressor failed for 12 hours, resulting in more emissions.

TCEQ is “evaluating” the emissions events at Sand Hills and Wildcat, the regulator said in a statement. “There are no current formal enforcement action being processed.” TCEQ last conducted an on-site investigation of Sand Hills in October, which resulted in a “notice of violation” for not reporting all emission events. The regulator hasn’t conducted an on-site investigation of Wildcat but has probed its emissions events, it said.

“The volume of emissions points to a complete failure at both plants,” said Colin Leyden, a director at Environmental Defense Fund. “We suspect that these large vents are happening frequently.”

Indeed, analysis of more than 200 reports made by Sand Hills to TCEQ of unauthorized pollution since 2019 shows that the plant pumped out even more emissions over three days in March 2020. In a filing, Targa said an acid gas compressor “shut down due to multiple mechanical failures” resulting in 444,010 pounds of sulfur dioxide emissions. That’s about 22 times the amount of sulfur dioxide Motiva’s Port Arthur refinery released during the Texas winter storm.

The culprit in the March 2020 event? The same acid gas compressor, CM-14.

So far, scrutiny of the shale industry’s environmental footprint has mostly focused on oil producers flaring and venting gas. For years, much of the industry preferred to burn the fuel or simply let it escape into the atmosphere rather than pay for the pipes and processing needed to bring it to customers.

With little oversight from Texas regulators, who famously went years without denying a flaring permit, the result was environmental damage and enormous economic waste. Producers flared or vented 1.47 billion cubic feet of natural gas a day in June 2019, according to Rystad. That’s enough to supply 11% of the entire country’s residential consumption. Burning gas turns it into carbon dioxide while venting emits methane, an even more potent greenhouse gas.

The Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent oil-price crash caused shale operators to cut production, leading to significantly less flaring. The good news is that even as output rebounds this year, upstream flaring is nearly 70% below its peak as operators respond to environmental concerns about the practice, according to Rystad.

The bad news is there has been no comparable reduction among gas processing facilities, which are typically owned by pipeline operators that have a lower profile among investors and the public, according to Rystad’s Abramov. They now account for about a third of all U.S. oil and gas flaring, with volumes little changed over the past three years, according to Rystad.

The measure passed last month by the Texas Senate, however, would require the owners of all power generators, transmission lines, natural gas facilities and pipelines to protect their facilities against extreme weather or face a penalty of up to $1 million a day. The bill still needs approval by the state’s House of Representatives.

“There needs to be much more oversight in the midstream,” said EDF’s Leyden. “There are 150 to 200 of these facilities across the Permian and obviously they’re capable of large emissions.”

–With assistance from Dave Merrill and Gerson Freitas Jr.