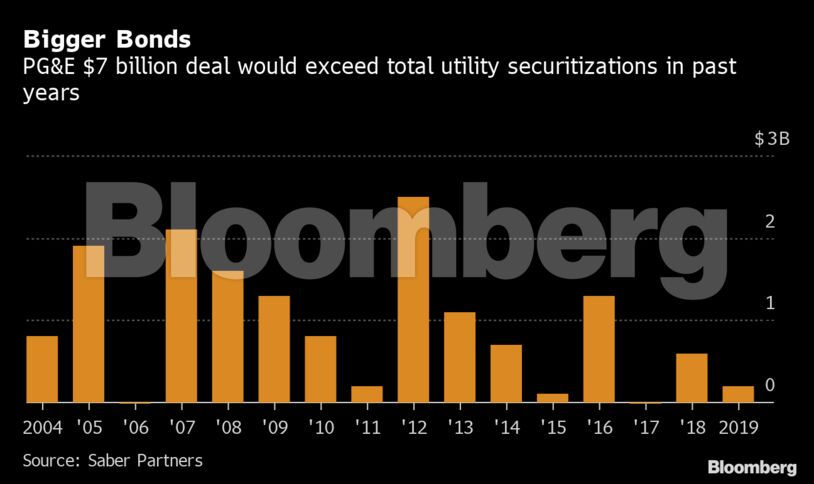

Fires and floods are sending some of the nation’s largest utilities to the bond market to cover huge, unexpected bills. California’s PG&E Corp., which was forced into bankruptcy a year ago after its equipment sparked the deadliest wildfire in state history, is seeking permission from the state to issue as much as $7 billion in bonds to cover claims. Meanwhile, North Carolina-based Duke Energy Corp. is putting together a bond deal to pay for almost $1 billion in repairs and other expenses from hurricanes and snowstorms that swept across Florida and the Carolinas.

“In the past, storms haven’t been at this magnitude, or this cost,” said Chris Bauer, director for credit and capital markets at Duke.

The deals underscore how climate change is driving up the expense of natural disasters for utilities. Power companies have always had to deal with wildfires and storms, but they’ve traditionally paid for the damages with modest rate hikes. As more extreme weather patterns trigger bigger and more frequent storms, the costs have skyrocketed. Utilities need a way to spread them out over years, and bonds—backed by a special line item charge on customers’ bills—are emerging as a potential strategy.

Storms have typically cost Duke in the tens of millions of dollars—no small amount, but part of the cost of doing business in the U.S. Southeast. But a series of extreme weather events in 2018 and 2019 caused unprecedented damage, and adding the full cost to bills would shock customers. Instead, Duke is putting together a deal to securitize the costs, issuing a bond that would be paid back over 10 years. While ratepayers still have to pick up the tab, spreading it out over a longer period makes the monthly bite more bearable. And because the notes are backed by a charge added to customers’ bills, the bonds are likely to get favorable financing terms, further reducing costs.

North Carolina approved the plan in November and Duke expects to complete the deal next year. Florida authorized a similar bond arrangement in 2015 after a repair at Duke’s Crystal River nuclear plant went awry and it had to be shut for good. The company securitized about $1.3 billion at an average rate of 3%, compared to about 6% return on equity that customers typically would pay. And Duke may consider using bonds to pay for closing coal-ash ponds in the Carolinas. Under a January settlement with state regulators, the project could cost up to $9 billion over 20 years.

“The amounts are so large that if you tried to use traditional financing, the rate shock would be too high,” said Joseph Fichera, chief executive officer of Saber Partners LLC, a New York advisory company. “This is where securitization comes to the rescue.”

In California, climate change has meant hotter, longer summers that bake vegetation and creates an almost year-round wildfire season. The November 2018 Camp Fire that killed 85 people was just one of a string of blazes that were ultimately tied to PG&E equipment, driving the company into bankruptcy with $30 billion in estimated liabilities. Its bond issue would be backed by a charge on customer bills and offset by credits from tax benefits and other sources, according to a filing with state regulators. The securitization financing would help improve PG&E’s credit metrics upon its emergence from Chapter 11, the company said.

“Absolutely, one of the motivations we’re seeing for securitization is for dealing with the impact of climate change,” said Uday Varadarajan, a principal with the Rocky Mountain Institute. “If an asset is destroyed or becomes useless, refinancing becomes a more attractive option.”

Utilities are also using bonds to close coal-fired power plants early. In Wisconsin, WEC Energy Group Inc. is putting together an offering now to refinance about $100 million for a plant it shuttered in 2018. And in Michigan, CMS Energy Corp. has issued about $390 million in bonds to cover costs from three coal plants it closed in 2016, and plans to issue additional bonds for other plants it’s expecting to shutter in the coming years.

The bonds make the whole process less expensive, said Sri Maddipati, CMS’s vice president for investor relations. But “ratepayers are still paying for it,” he said.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Poll: Consumers OK with AI in P/C Insurance, but Not So Much for Claims and Underwriting

Poll: Consumers OK with AI in P/C Insurance, but Not So Much for Claims and Underwriting  MGM Resorts Sues US FTC to Stop Investigation of Casino Hack

MGM Resorts Sues US FTC to Stop Investigation of Casino Hack  Bridge Disaster in Baltimore Gets FBI Criminal Investigation

Bridge Disaster in Baltimore Gets FBI Criminal Investigation  Justice Department Preparing Ticketmaster Antitrust Lawsuit

Justice Department Preparing Ticketmaster Antitrust Lawsuit