Thinning ice in the Arctic Ocean made this year’s navigation season for natural gas tankers the longest on record, the latest sign that the pace of climate change is accelerating in the Earth’s northernmost latitudes.

The Northern Sea Route, stretching more than 3,000 nautical miles between the Barents Sea west of Russia and the Bering Strait in the country’s east, traditionally opens from June through October, when higher temperatures break up ice. This year, voyages started a month early and will continue until at least the end of December. Record warmth meant slower freezing during the autumn.

“This year could potentially become a turning point for the Arctic,” said Samantha Burgess, deputy director at Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. “This was a fairly exceptional year in that the warmer-than-average condition was incredibly persistent throughout the whole year.

The length of the shipping season in the Arctic is one of the most tangible signs that the region is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the world. In a year that’s likely to rank among the three warmest on record—if not the hottest ever—it’s the Arctic that registered the most notableincreases in what is emerging as an enormous climate-related disaster.

The length of the shipping season in the Arctic is one of the most tangible signs that the region is warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the world. In a year that’s likely to rank among the three warmest on record—if not the hottest ever—it’s the Arctic that registered the most notableincreases in what is emerging as an enormous climate-related disaster.

Temperatures of more than 5 degrees Celsius above average for the first 10 months of 2020 fueled the most active wildfire season on record. High atmospheric temperatures led to an increase in water temperatures. Sea ice extent was the lowest on record for the month in July and October, and the second-lowest for most of the year. Thawing permafrost is threatening strategic oil, gas and civilian infrastructure in northern Russia, Canada and Alaska

What’s bad for the planet is an opportunity for the $100 billion-a-year liquefied natural gas industry, the quickest growing part of the fossil fuel business. To ship the fuel across an ocean or beyond where pipelines reach, the gas is chilled to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 160 Celsius) until it turns to a fluid.

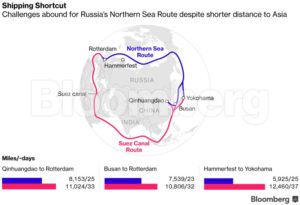

The trade in LNG cargoes has surged in recent years, boosting the stream of tankers moving the commodity from fields in Africa, the Middle East and Australia to lucrative markets mainly in Asia. Melting ice in the Arctic reduces shipping costs for cargoes that would otherwise have to transit the Suez Canal or the southern tip of Africa.

To the west, the Barents and Kara Seas remained largely free of ice as late as November, according to Copernicus, the European Union’s climate satellite program. To the east, ice cover in the Chukchi Sea between Russia and Alaska has dropped by more than 45% since the late-1970s, according to Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

The longer the Northern Sea Route stays open, the more LNG cargoes can head directly to Asia, where it is consumed by industry and power generators in China, Japan and South Korea. Russia and the LNG industry are working to extend that shipping season, deploying the world’s biggest icebreaker starting in October to escort tankers for more months of the year.

“Undoubtedly, such early and late navigation brings us closer to the implementation of one of the key goals of the Northern Sea Route development strategy—year-round navigation,” said the press office of Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned nuclear corporation in charge of managing the route.

The nuclear-powered Arktika is capable of breaking through ice up to 2.9 meters thick (just under 10 feet), almost a third more than the current generation of ships in the Russian fleet. That will help Novatek PJSC move LNG cargoes to market from its giant fields on the Yamal peninsula in northern Russia

The Arktika will accompany ice-class LNG carriers to help make a path through this route and may enable a few journeys to Northeast Asia over December and through as late as April, consultants Energy Aspects Ltd. said in a note in November.

This year’s extraordinary climate conditions have already allowed for a record number of voyages to Asia through the Northern Sea Route. About 30 will be made this season, five more than initially forecast, Mark Gyetvay, chief financial officer at Novatek said in November. That compares with 17 in 2019 and four in 2018. One last ship may finish the voyage through the Arctic route to Asia this month.

For years, the gas industry and LNG exporters have promoted their fuel as a cleaner-burning alternative to coal. Novatek says its LNG plant is among the most efficient in the world, with some of the lowest carbon and methane emissions. It also uses tankers that burn LNG instead of ship oil, dramatically reducing pollution from its vessels. But while gas delivers lower carbon emissions than any other fossil fuel, policy makers worldwide are increasing their scrutiny of the business as they work toward slashing emissions that damage the atmosphere

The LNG industry’s success in the Arctic is a concern for scientists and environmental groups, who see a “feedback loop” with more ships speeding up the pace of warming in the region. The ice’s white surface reflects sunlight and helps cool the atmosphere. When it melts, it is replaced by ocean water, which is dark and absorbs solar radiation.

More shipping traffic in the Arctic also brings higher emissions of polluting gases, which can boost temperatures and soften ice packs locally, Burgess said. The presence of the tankers also increases the risk of accidents and spills in an area where biodiversity is fragile, she said.

“There’s a strong interest to take advantage of the more efficient shipping route,” Burgess said. “Equally, it’s important that there’s policy put in place to make sure that’s done legally and safely, with adequate measures put in place to protect these vulnerable ecosystems.”

–With assistance from Dina Khrennikova.

About the photo: Arktika, the world’s biggest icebreaker, readies for operations in the Arctic in December. Source: Rosatom